Today’s Post by Joe Farace

Always bear in mind that your own resolution to succeed is more important than any other. —Abraham Lincoln

When it comes to capturing digital infrared images, you have several options: One of the easiest and least expensive is by using on-camera filters. That’s the upside, the downside is that there are one big disadvantages to this method, which boils down to the high filter factor—filter density—that will produce, sometimes extremely, slow shutter speeds absolutely requiring the use of a tripod.* Not, as Seinfeld once say, “that there’s anything wrong with that.”

If you want to shoot infrared images hand held, one of the tips that I give photographers who are interested in getting started with infrared photography is that they should convert an old camera that’s just sitting around collecting dust to IR-only capture. The theory being that you’re not shooting with it anyway so why not get a unique use from something that’s probably not worth much either. Yet its conversion cost will add to its worth both as a camera you can use to make fun images right now and it’s real-world value will increase if and when you ever decide to sell it.

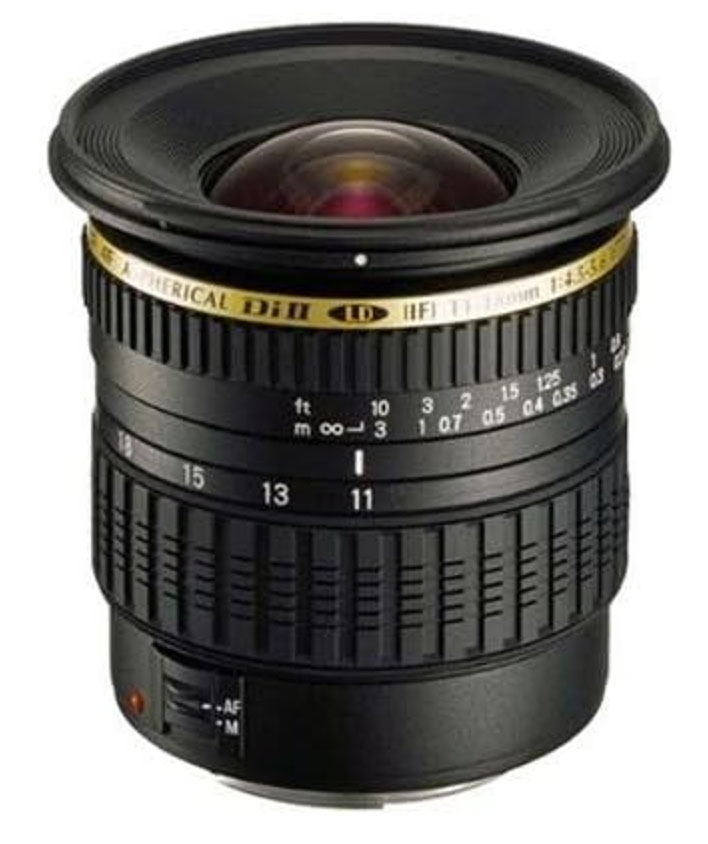

How I made this photograph: The above image was made near Brighton, Colorado with a used Canon EOS D60—not a 60D—that had been converted to infrared capture by its previous owner by a company who converted my original EOS D30 to IR. That company is no longer in business; they took six months to convert my D30. The lens used was the Tamron 11-18mm f/4.5-5.6 at 11mm. Exposure was 1/90 sec at f/16 and ISO 400 and the image file was converted to monochrome using Silver Efex for a pretty straightforward monochrome conversion.

Playing the IR Game

I’ve always envied photographers who had the financial wherewithal to have the latest high-end, high megapixel cameras converted to infrared so they could capture the highest possible resolution images, at least until the next model comes along. That’s never happened to me. And most of us don’t have that kind of money for what is, to put the best possible spin on in, such a niche pursuit. That’s why I think my above suggestion abiut using an old camera is a good one.

I’ve always envied photographers who had the financial wherewithal to have the latest high-end, high megapixel cameras converted to infrared so they could capture the highest possible resolution images, at least until the next model comes along. That’s never happened to me. And most of us don’t have that kind of money for what is, to put the best possible spin on in, such a niche pursuit. That’s why I think my above suggestion abiut using an old camera is a good one.

One way that I personally get around any resolution anxiety related to photography with older, lower resolution cameras is to shoot all my infrared images in RAW format. Unlike JPEGs, capturing a RAW file requires little or no internal camera processing. These files contain much more information but now that data will require processing and since most of the time you’re going to have to process a infrared file anyway, what’s the big deal? I should mention that there’s a SOOC (Straight Out Of the Camera) movement popular in some infrared circles and the images produced that way can be interesting. And while I sometimes will use this approach, I typically don’t.

*filter factor: According to Analogue Wonderland, “A filter factor is a unit of measurement that tells us how much you need to increase the exposure when using a particular filter, this is done by multiplying the unfiltered exposure by the filter factor. For example, a filter factor of two means you will need twice as much exposure. Yes, some of the newer DSLRs and mirrorless cameras have eight stops of in-body image stabilization but IR filters are so dense you can’t see, or it’s difficult to see, through the filers. If your camera is on a tripod you can compose the shot, screw on the filter and make the exposure. Hand held that task will be much more difficult to accomplish, at least for me as Señor Wences used to say.