My Sunday series on outdoor portraiture continues with a portrait of Mina, a model I photographed twice over two years during a series of group model shoots that were held in Phoenix. Arizona. Today’s featured Image is from our first shoot.

Today’s Post by Joe Farace

Colors, like features, follow the changes of the emotions. — Pablo Picasso

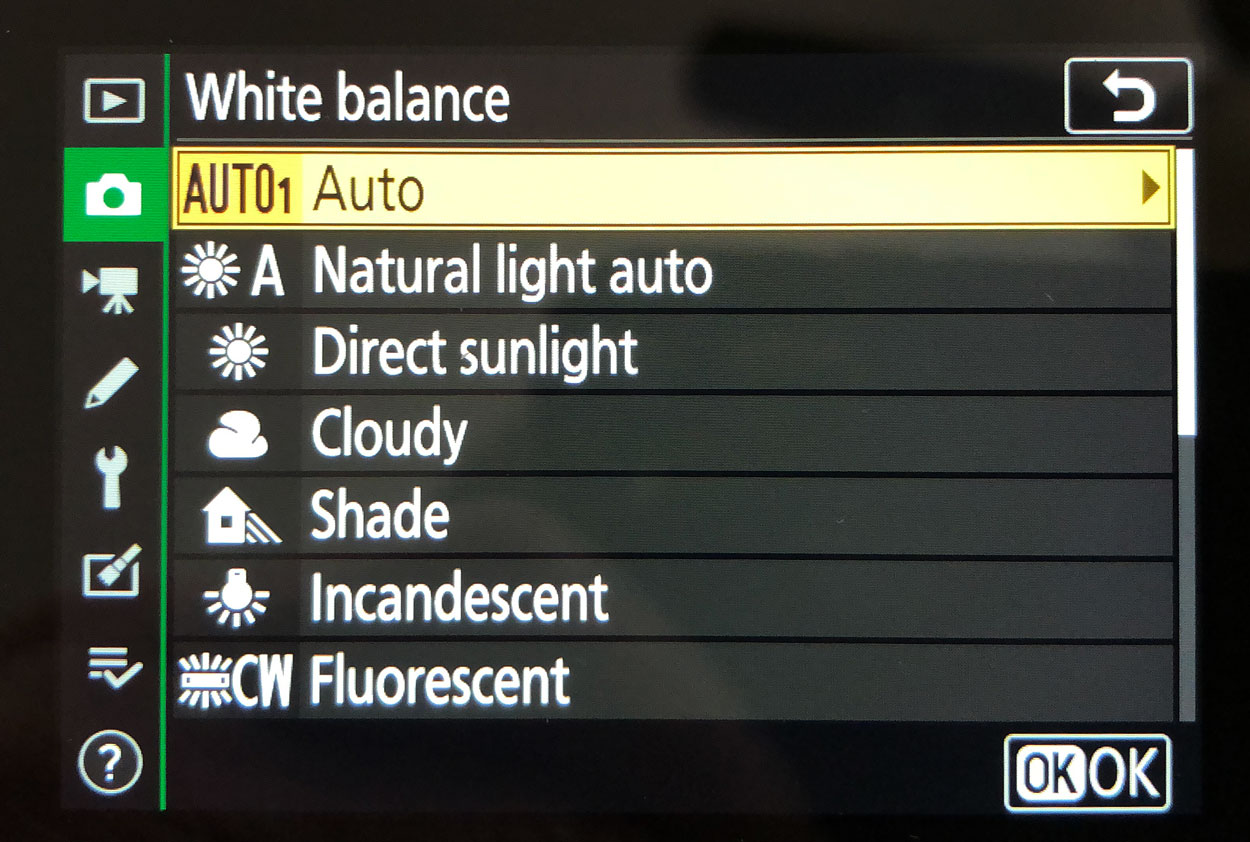

White Balance is a topic I often return to in this blog. Let’s take, for example, the incandescent— sometimes called tungsten—setting that can be found found in DSLRs or mirrorless cameras. It’s primarily used for those times when you’re making photographs under quartz or photoflood lamps that have a color temperature of 3200K. It will also work when working under household lamps whose color temperature varies depending on the light’s wattage but typically hover around 2800K. This setting is designed to cool off the color of the light and can offer some other fun usage, such as to add a chilly blue look to a scene with images made in snow.

White Balance is a topic I often return to in this blog. Let’s take, for example, the incandescent— sometimes called tungsten—setting that can be found found in DSLRs or mirrorless cameras. It’s primarily used for those times when you’re making photographs under quartz or photoflood lamps that have a color temperature of 3200K. It will also work when working under household lamps whose color temperature varies depending on the light’s wattage but typically hover around 2800K. This setting is designed to cool off the color of the light and can offer some other fun usage, such as to add a chilly blue look to a scene with images made in snow.

A camera’s incandescent color balance setting is amazingly useful. It’s like loading a 35mm film camera with tungsten-based color film, such as such as Kodak Vision3 500T or CineStill 800T. You can also use this setting outdoors with a filtered flash to create a, sort of, special looks. One of my favorite techniques for using a camera’s incandescent setting is for outdoor portraits because just because a camera offers a incandescent setting doesn’t mean you can’t use it outdoors.

How I Made this Portrait

This portrait of Mina was made outdoors on a movie set in Phoenix. The camera was in the incandescent (tungsten) White Balance mode, which accounts for the extra blueness of the sky and background.This image was made using a Canon EOS D60—not 60D—with an EF 28-135mm f/3.5-5.6 lens (at 28mm) with an exposure of 1/200 second at f/14 and ISO 200.

This portrait of Mina was made outdoors on a movie set in Phoenix. The camera was in the incandescent (tungsten) White Balance mode, which accounts for the extra blueness of the sky and background.This image was made using a Canon EOS D60—not 60D—with an EF 28-135mm f/3.5-5.6 lens (at 28mm) with an exposure of 1/200 second at f/14 and ISO 200.

A Canon 420EX speedlite was used with an orange (85A) Rosco gel filter covering it flash head. I wanted to place the subject out in the middle of this area not only to show the background but also to prevent the filtered flash from hitting any background objects and spoiling the effect. I tried several poses and bracketed exposures and this pose—admittedly uninspired—seemed to work best. This technique takes a little practice and success ultimately depends on the speedlight’s power output and how “correct” the gel is to get a specific effect. Thanks, and a tip of the Farace chapeau to Barry Staver for introducing me to this technique.

The light from different electronic flash units—whether studio lights or speedlights—tends to be cooler than daylight so you can use this setting to warm up many of your flash images. For some cameras the incandescent White Balance setting is similar to the Cloudy setting and some photographers use both as a form of digital warming filter. The way each camera manufacturer handles their speedlight’s color balance can vary and based on my experience I’ve found that Nikon and Canon’s flashes behave differently, with Nikon’s tending to be slightly warmer than what some would consider “normal.” Although when it comes to color balance one photographer’s “warm” is too cool for another.

Coming tomorrow: More about using White Balance settings, this time for infrared photography.

If you enjoyed today’s blog post and would like to buy Joe a cup of Earl Grey tea ($3.50), click here. And if you do, thanks so very much.

If you enjoyed today’s blog post and would like to buy Joe a cup of Earl Grey tea ($3.50), click here. And if you do, thanks so very much.

Barry Staver and Joe Farace are co-authors of Better Available Light Digital Photography with new copies available from Amazon for $21.50 or used copies at giveaway prices, starting around ten bucks, as I write this. The prices of Kindle copies, for some reason, vary.