I stole the idea for “Things I Promised Not to Tell” from a political podcaster but no posts in this series will be about politics. Instead it will feature vignettes from my personal, sometimes non-photographic, life that may or may not have made me into the person I am today. Especially today’s post….

Today’s Post by Joe Farace

“Cancer is just a chapter in our lives and not the whole story.”— Allie Moreno

Before some of the events that I’ve mentioned in other posts in this series, something happened that changed my life forever; I got cancer. It was Hodgkin’s Disease, a type of lymphoma that is a blood cancer that starts in the lymphatic system.

Much like the Spanish Inquisition, nobody expects to get cancer, especially when they’re they’re (relatively) young and riding an exhilarating wave, that consider the most creative period of my life. Sometime around 1972 I developed what seemed to be flu-like symptoms except it didn’t get better or go away. Gradually I grew weaker and my (then) wife took me to see our family doctor. While sitting in the waiting room I picked up and read a pamphlet entitled “The 10 Warning Signs of Cancer” and realized I had eight of the symptoms but couldn’t believe I had the disease. I was too young and that kind of bad stuff only happened to other people, not me. After a cursory physical examination the doctor called St. Agnes Hospital, that was located next to his office, and had me admitted immediately for tests with a preliminary diagnosis of anemia.

That was Monday morning and over the next several days, I was subjected to a biopsy and some tests some that were more bizarre and painful than anything I’d previously experienced. This was the early seventies and believe me, medicine (and cancer treatment) has changed a lot since then. On Friday night of that same week, Dr. Raymond Bahr walked into my hospital room and informed me that I had Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, a cancer originating from white blood cells called lymphocytes. The disease was named after Thomas Hodgkin, who first described abnormalities in the lymph system in 1832.

That was Monday morning and over the next several days, I was subjected to a biopsy and some tests some that were more bizarre and painful than anything I’d previously experienced. This was the early seventies and believe me, medicine (and cancer treatment) has changed a lot since then. On Friday night of that same week, Dr. Raymond Bahr walked into my hospital room and informed me that I had Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, a cancer originating from white blood cells called lymphocytes. The disease was named after Thomas Hodgkin, who first described abnormalities in the lymph system in 1832.

My immediate response to this news was to cry and feel sorry for myself: How could this happen to me? I’d never have the chance to do all the things I wanted to do in my life. I’d never been to France, as the song goes. (I did make it to Paris in 1978.) Dr. Bahr immediately sensed my mood and told me that the next day they were going to try a new kind of cancer treatment called “chemotherapy” and he looked me in the eye and promised that afterwards I would “feel better than I had in a long time.” That statement turned out not to be true and the outcome was not without the inevitable side effects.

I won’t bore you with the eighteen months of chemotherapy I underwent and the side effects that sometimes felt as bad as the disease. Nowadays the way chemotherapy is administered is more humane and quite different than it was back then but the side effects are still physically and mentally traumatic for the patient. I saw how the current process works up close and personal when Mary was diagnosed with breast cancer 20 years ago. (She is cancer-free now.)

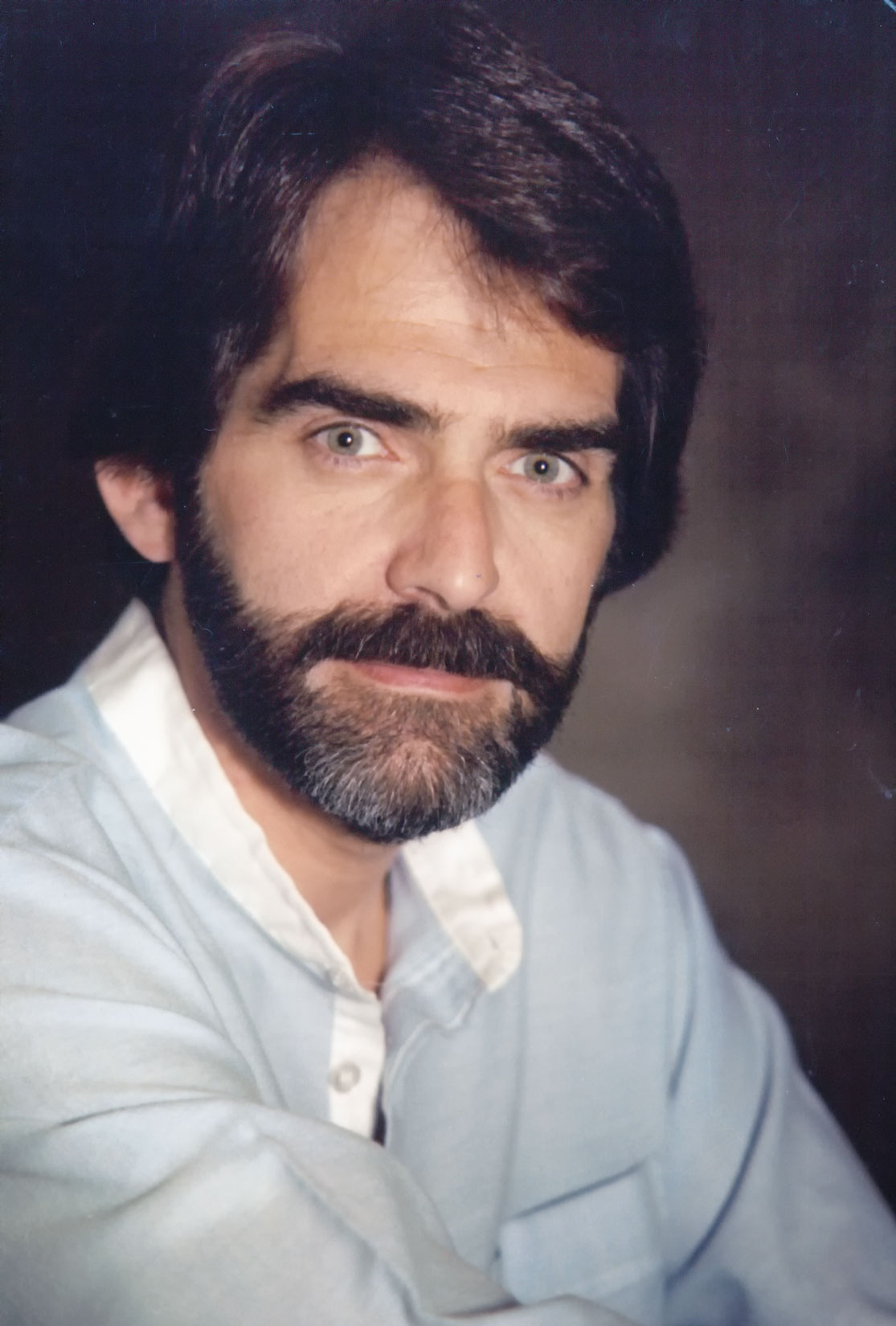

After treatment there was a change inside and outside of me as well. During the several weeks I was in the hospital I grew a beard. I had always wanted to have one and if I wasn’t going to make it, I didn’t want to have to shave every day. I also had an attitude shift. My tolerance for bullshit, always on the low end of the Richter scale, became even less so.

You see, before cancer entered my life I had a interesting meeting with the chairman of the Photography Department at the Maryland Institute of Art. After reviewing my portfolio he encouraged me to go to art school full-time to engage my perhaps naive goal of becoming a fine art photographer. As an engineer I knew that somewhere along the line I would have to figure out how to make a living with my photography. Before I had cancer, the reaction from the friends and family who I talked with about this goal was unanimous: “Are you crazy?”

After finishing chemotherapy and returning to what would become ultimately become something like “normal” life—whatever that is— for the next several years, I again brought up that same subject to those very same people. The reaction from all of my friends and family that I talked with was unanimous: “Are you f***ing crazy!”

How did this reaction affect my photography or what could laughingly be called my photographic career? For some time I was frustrated by these responses but was rescued by some upcoming events that occurred toward the end of 1970’s. But that’s another story…