Today’s Post by Joe Farace

At times our own light goes out and is rekindled by a spark from another person. Each of us has cause to think with deep gratitude of those who have lighted the flame within us. —Albert Schweitzer

Whenever I teach a photography workshop or seminar, no matter what the ostensible subject may be discussing, the topic of exposure always comes up. Ultimately the answer to that question comes down to one word: latitude. My definition of exposure latitude is that it’s a measure of how much an image captured either by film or an digital sensor, can be overexposed or underexposed and still produce an acceptable result.

These days not every photographer started out by shooting with a film cameras but an understanding of exposure latitude, even with a digital camera, can be enhanced with just a little bit of information about how film worked back in the day and still works today. For example…

How I made this shot: I made the photograph of the Brighton, Colorado City Hall using a Canon EOS 1D Mark II N and with Canon’s EF 22-55mm f/4-5.6 USM EF lens. The image you see is actually a combination of two exposures: The first one covers everything from the right side of the large tree on the left) to the right edge of the frame: it had an exposure of eight seconds at f/13 at an ISO of 200. The second exposure from that same tree to the left edge of the frame was made at 2.5 seconds because the tree and city hall sign were too overexposed for my taste, anyway.

How it Works

Slide aka transparency film has the least amount of latitude, especially even slight overexposure can wash out all or parts of any image. While color negative aka print film has much more latitude on the underexposure side, sometimes amazingly so. In fact slight over exposure of color negative can “richen” the look of the photograph. The imaging sensor in your DSLR or mirrorless camera seems to respond to exposure much like a hybrid of the two different kinds of color film: Overexposure wipes out image data but underexposure has much more latitude, almost as much as film. The downside of any underexposure is the inevitable creation of digital noise, especially in the shadow areas, behaving much the same way as emphasizing grain might have done with film.

What is Correct Exposure?

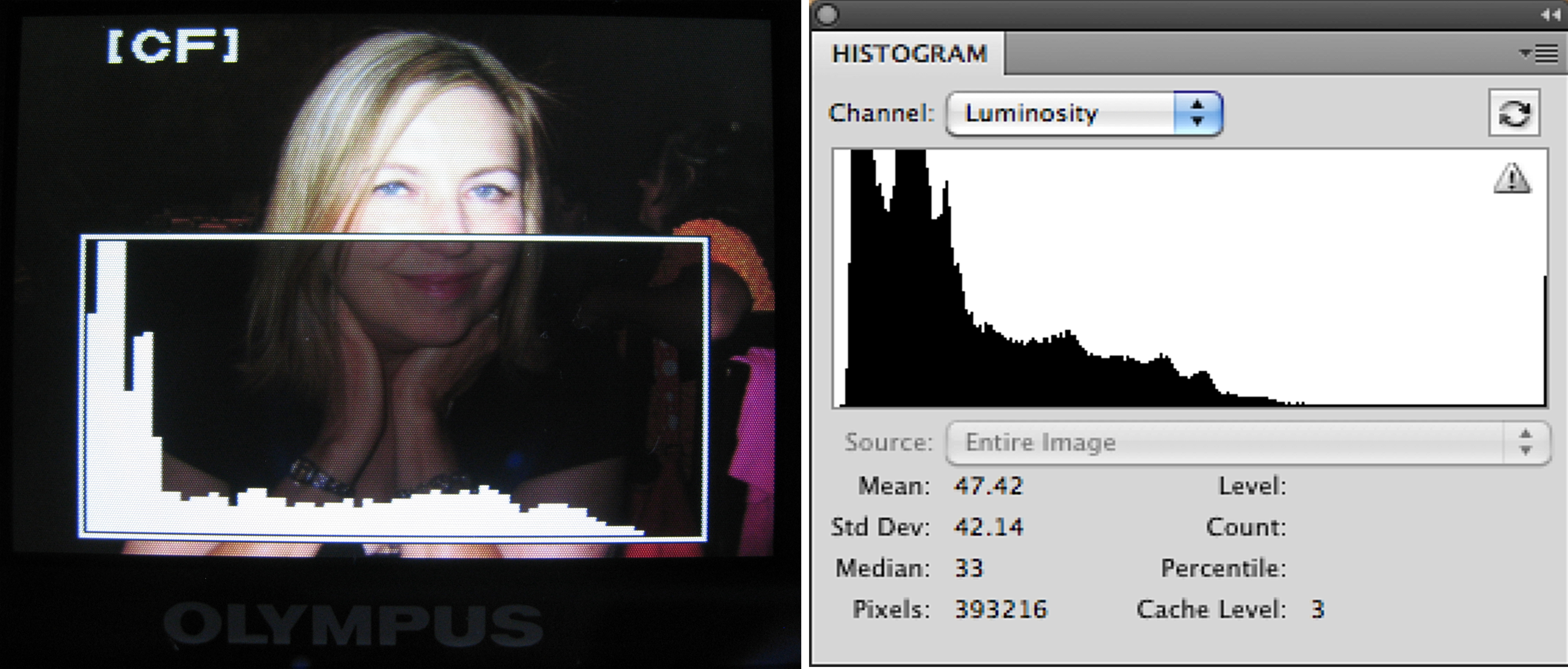

My personal feeling is that you are the final arbiter of what is “correct” exposure. If you want to get more technical, one way to evaluate a particular image’s exposure is by using your camera’s histogram function. Check your User’s Guide for information how to display a histogram on the camera’s LCD screen. Some mirrorless cameras will even let you display it in real time before capture in the electronic viewfinder.

An image’s histogram appears on a camera’s LCD screen (or EVF) as a graph displaying the photograph’s range of brightness from highlight to shadow in 256 steps. Zero is on the left size of the graph and represents pure black; 255 is on the far right-hand side and represents pure white or the famous shot of a “Polar Bear in a Snowstorm.” In the middle are the mid-range values representing grays, as well as browns and greens.

On a typical photograph, all of a photograph’s tones will be captured when the graph rises from the bottom left corner, peaks in the middle, then descends towards the bottom right producing what statisticians call a bell-shaped (aka Gaussian) curve because it’s, well, shaped like a bell.

On a typical photograph, all of a photograph’s tones will be captured when the graph rises from the bottom left corner, peaks in the middle, then descends towards the bottom right producing what statisticians call a bell-shaped (aka Gaussian) curve because it’s, well, shaped like a bell.

If the histogram’s curves starts out too far in from either side or the slope appears cut off, then data is missing or the image’s contrast range exceeds the camera’s capabilities to capture what you saw with your eyes. While the classic histogram features a bell-shaped curve, not every photograph fits this type of distribution. Dramatic images with lots of light or dark tones areas often have lopsided histograms but that doesn’t mean they aren’t good photographs.

Along with photographer Barry Staver, Joe is co-author of Better Available Light Digital Photography that’s out-of-print but new copies are available from Amazon for $21.49 with used copies starting at five bucks, as I write this.